Pedro Xavier: A New Generation Emerges.

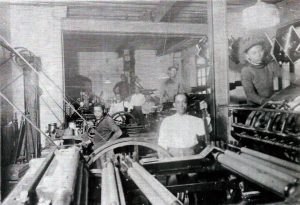

On the death of his father in May 1909, six months before his twenty-third birthday, Pedro Xavier became president of the Hongkong Printing Press. In the year that followed, while settling the business affairs of the firm, which employed family members and local Chinese, as well as Lisbello Xavier’s estate, Pedro devised a strategy that would lead in a new direction. Not every move met with success. However, important adjustments to the Press’ operations during Pedro’s tenure could be considered forward thinking among Macanese printers.[1]

The most significant change involved moving from lithographic production to offset printing, a new technology developed around 1901 that produced four color reproductions and allowed security measures to be incorporated into the process.[2] This strategy led to several new product lines that went beyond government notices that defined the Press’ early years. These included newspapers, magazines, brochures, stationery, and books, as well as labels for consumer goods moving through Hong Kong and the other “Treaty Ports”. Another lucrative line were private bank notes issued by institutions supporting the large bulk of trade, which relied on currencies backed by bullion to safeguard commercial and individual transactions. The effect of these new ventures will be discussed in more detail below.

In isolation, however, the change in products offer few clues to the significance of Pedro’s activities as a businessman and a social actor in early 20th century Hong Kong. To explore this aspect in more detail, we will suggest where Pedro’s pursuits “fit” in relation to other Macanese, including printers who were well positioned during the period. We will also consider the larger contexts of Hong Kong’s development and changes affecting Macau during the same period, each of which influenced how the Press and other Macanese businesses operated. As we proceed, a closer review of Pedro Xavier’s leadership in business and his involvement in the Portuguese community from 1909 to 1941 will provide dual lenses from which to observe him navigate the rough environment of British Hong Kong and the deterioration of China during those years.

A Short Introduction

As the eldest of Lisbello Xavier’s eleven children, Pedro d’Alacantara Xavier was born in Hong Kong on October 19, 1886 while his father was still employed by Delfino Norohna’s printing company. Pedro was educated with other Portuguese students at St. Joseph’s College in central Hong Kong by French Lasallian priests (also known as the “Christian Brothers’’), the same order that taught his father in Macau. It was likely that Pedro took both primary and secondary courses at St. Joseph’s, since the latter were not offered separately until the founding of La Salle College in 1917. By then Kowloon had grown to become home to many Macanese families, including the Xavier’s residence on Barrow Terrace (now Grandville Road).

As the eldest of Lisbello Xavier’s eleven children, Pedro d’Alacantara Xavier was born in Hong Kong on October 19, 1886 while his father was still employed by Delfino Norohna’s printing company. Pedro was educated with other Portuguese students at St. Joseph’s College in central Hong Kong by French Lasallian priests (also known as the “Christian Brothers’’), the same order that taught his father in Macau. It was likely that Pedro took both primary and secondary courses at St. Joseph’s, since the latter were not offered separately until the founding of La Salle College in 1917. By then Kowloon had grown to become home to many Macanese families, including the Xavier’s residence on Barrow Terrace (now Grandville Road).

At age sixteen Pedro left St. Joseph’s to work as a bookkeeper for a German merchant, Carlowitz & Co. German traders had been active in Canton since 1783, headquartered first to Macau, then moved to Hong Kong in 1859 during the last stages of the Opium Wars.[3] In June 1904 through April 1906 Pedro worked for his father’s printing business, then joined the Kowloon-Canton Railway Co. as an assistant bookkeeper, and was quickly promoted to “Head Correspondence Clerk”. Pedro returned to the Press for good, however, in September 1906, working as a compositor until his father’s death less than three years later.

Information and Commerce in the Treaty Ports

During Pedro’s early years he understood that the Press benefited from the high demand for information in Hong Kong, which was a catalyst for business. His father had seen in the decades after the Opium Wars that merchants, governments, and missionaries relied heavily on printed reports and government notices to operate through several “Treaty Ports” conceded by China. The Pearl River Delta became the nexus of the first network, beginning with the establishment of the British East India Company’s press in Canton in 1814 and printing at St. Joseph’s College Seminary in Macau in 1826. As Hoi To Wong writes: “Access to knowledge about China was essential to create an information network for merchants and missionaries… Printing was a key to the circulation of information and knowledge in the form of pamphlets, books, newspapers, and periodicals.”.[4]

By the 1860s, the growth of commerce in Hong Kong and Shanghai became the main stimulus for large numbers of Macanese to be trained in typesetting. As mentioned in the previous study, Delfino Noronha was one of the pioneers in this new field, and Lisbello Xavier was one of his successors. High concentrations of Macanese printers could be found in Shanghai, Hong Kong, and other ports along the southern coast of China.[5] Through the end of the 19th century Macanese printers dominated the industry, taking over businesses started by Britons and other Europeans, and inspiring a boom in journalism, business news, and pamphleteering that became critical to the expansion of international commerce.[6] Their virtual monopoly on the production and distribution of printed information in Southeast Asia quickly reached global proportions with the involvement American and European companies by the 1870’s, increasing the pace of China’s foreign trade.

The variety of goods passing through the treaty ports reflected these changes. In the decades following 1840 traditional goods like spices, tea, silk, opium, and porcelain were supplemented by cotton, textiles, metals, machinery, sea products, dry foods, oils, vegetables, medicinal products, stone, and fuel. Virtually all information related to these products published in newspapers, government notices, and advertising were set to type by former residents of Macau. Even reports to shareholders and ship manifests of goods passing through each port were reproduced by Macanese printing companies. Hong Kong, the center of Britain’s holdings in East Asia, accounted for one quarter of all China’s imports and exports.[7] Economists Wolfgang Keller, Ben Li, and Carol Shiue estimated that between 1868 and 1947 commercial activity in China grew rapidly at 6.4% per year. In comparison, the Post-World War II boom in the United States grew at a lower rate of 4.1% from 1945 through the 1980s.[8]

While remaining in the printing business, Pedro Xavier attempted to take advantage of Asia’s economic boom. But like all Macanese, he also was drawn to developments in Macau.

Macau after the Opium Wars

In contrast to Hong Kong, Macau suffered from a number of social and political setbacks that restricted its economy. The commercial printing industry had already abandoned the city for Canton, Hong Kong, and Shanghai in the 1840s as a result of threats to commerce by the Chinese government, which led to the Opium Wars.[9] In the years up to the outbreak of World War I, colonial authorities in Macau sought a precarious balance between the distant supervision of Lisbon, political pressures from Imperial China, which was itself under siege by opium traders, and divided interests within the municipal administration.[10]

At the center was a struggle to define Macau’s position in relation to China as the Manchu government crumbled. Sensing China’s weakness, in 1849 the municipal council attempted to proclaim its sovereignty, but was beset with rebellions among local Chinese and the assassination of Governor Ferreira do Amaral. Some resolution was achieved in 1887 with the signing of the “Treaty of Friendship and Commerce” between Portugal and China, but resulted in limited recognition of Macau’s permanence and “dual jurisdiction” so long as both policies remained acceptable to China’s Imperial government.[11]

Equally significant were attempts to use dwindling resources after many merchants abandoned Macau for more secure territories. One of the treaty’s requirements was that Macau control the trading of opium in the territory. This not only threatened one of Macau’s three main industries (opium, gambling, and contracted labor), but also the Portuguese monarchy’s efforts to maintain a colonial presence in Africa. The opium stipulation was basically ignored by Macanese administrators up to and after the October 1910 overthrow of King Manuel II and the installation of a Republican government in Lisbon.[12] Recent historiography indicates that at least one of Macau’s governors, Anibal Augusto Sanches de Miranda, actively defended the preservation of the local government’s monopoly on drug sales at an international opium convention in 1912.[13] Shortly after, the government in Lisbon persuaded Macau’s council to use opium profits to “loan” it 270,000 (MOP) to defend interests in Angola.[14] Thus, opium together with gambling and the coolie trade took on added weight as alternative sources of revenue in place of a broader mix of commodities traded elsewhere.

Life inside Macau, however, remained relatively calm in the eye of the storm created by British Hong Kong. Local perceptions of the two territories were simpler, as captured by Manuel da Silva Mendes, a journalist writing in 1919, who observed:

Whoever puts as the main purpose of your living (is to) earn money, you will feel that you live better in Hong Kong than Macau. … Anyone who does well in the midst of the great movement, hustle and noise, will like the life of Hong Kong more. …, but in this case the point is misunderstood. … Cities like men, are not measured by spans, like donkeys because they have big ears. … the superiority of Hong Kong over Macau, taking away its trade and relative parts, consists of mainly of having larger ears. Macau is an old city, but despite this, or even for that reason, it is … far superior to Hong Kong.[15]

The implied tensions created by a “modern” life dependent on commerce and a “traditional” life in the cultural homeland remained a feature of Macanese identity for many years.

A New Generation in Hong Kong

Despite Macau’s “inferiority”, and perhaps acknowledging its traditional embrace, many immigrants continued their connection to the Portuguese colony, often blurring the line between culture and business.[16] In 1910, for example, shortly after becoming president of the Hongkong Printing Press, Pedro Xavier was elected a director of the Royal Aerated Water Manufactory Co., a soda beverage company in Hong Kong. It was no coincidence that the company was managed by Francisco de Paula Danenberg, whose family was from Macau and a relative by marriage.[17] It seems likely that the firm’s Macanese manager and the new director utilized familial connections to conduct business in the Portuguese territory, including the printing of soda labels. Pedro also remained a member of the Club de Recreio, the association founded by his father in 1903, and served on a leadership committee. The club had become a central part of the Macanese community in Kowloon since being ceded by China in 1860. By 1916 Pedro also was a member of two organizations associated with republican causes in Macau and Lisbon: the Liga Portuguese and the Royal Geographic Society of Lisbon. Both were active in programs involving soup kitchens, education, and funds for war veterans and their families. Pedro is reported to have donated $10,000 HKD to support wounded soldiers who survived the Battle of Flanders in which 7,000 Portuguese were killed.[18]

Within this milieu Pedro Xavier was able to identify new opportunities, partially a result of his social contacts and his ability to anticipate untapped markets. According to family records, there are indications that he prepared in advance. On August 5, 1913 Pedro sold the Hongkong Press offices at #3 Wyndham Street to the South China Morning Post for $55,000, gaining a profit of $15,000 on the sale. The next day the firm purchased #31 Wyndham Street, a three story building with 21 rooms and a large basement, for $69,000. The Press also began renting space for $800 monthly.[19] The larger building was to accommodate modern printing presses intended to produce currency notes and other security items for banks located in the region near Swatow (Shantou), a treaty port 300 kilometers north of Hong Kong in Guangdong.[20] Initially a landing spot for American missionaries, Swatow became known for hand embroidered table linens, silk lingerie, and handkerchiefs crafted by Chinese women using local silk and cotton obtained from India. By 1941, the industry was estimated to employ 300,000 workers producing goods for European markets. [21] As both a manufacturing and transportation hub for central China, Swatow offered a fertile environment for investors.

Within this milieu Pedro Xavier was able to identify new opportunities, partially a result of his social contacts and his ability to anticipate untapped markets. According to family records, there are indications that he prepared in advance. On August 5, 1913 Pedro sold the Hongkong Press offices at #3 Wyndham Street to the South China Morning Post for $55,000, gaining a profit of $15,000 on the sale. The next day the firm purchased #31 Wyndham Street, a three story building with 21 rooms and a large basement, for $69,000. The Press also began renting space for $800 monthly.[19] The larger building was to accommodate modern printing presses intended to produce currency notes and other security items for banks located in the region near Swatow (Shantou), a treaty port 300 kilometers north of Hong Kong in Guangdong.[20] Initially a landing spot for American missionaries, Swatow became known for hand embroidered table linens, silk lingerie, and handkerchiefs crafted by Chinese women using local silk and cotton obtained from India. By 1941, the industry was estimated to employ 300,000 workers producing goods for European markets. [21] As both a manufacturing and transportation hub for central China, Swatow offered a fertile environment for investors.

In the years from 1913 through 1940, the Hongkong Printing Press contracted with at least fourteen (14) private banks to produce currency notes of various denominations. Eight banks were headquartered in Swatow.[22] Five others were in Guangdong, Kwangtung, Fijian, and Fukien. In an especially active period from 1916 to 1921, Pedro Xavier is reported to have traveled to Swatow six times to secure bank contracts. Interestingly, during the same period he acquired a contract to print currency notes for Macau’s Banco Nacional Ultramarino, while also printing labels for the municipal government. Several years later it was revealed in a letter to the British Consul in Macau that the Press actually had been producing duty tax stamps for opium, liquor, and toilet articles since 1918.[23] Despite local restrictions, family connections and new markets continued to be lucrative in the next decades. [24]

A Revised Strategy

The business of printing currency, checks, and script was apparently profitable enough to begin a re-evaluation of HKPP’s core strategy. In October 1922 Pedro Xavier indicated this change of course by giving up the production of the Hong Kong Government Gazette and official notices altogether, selling the concession to two Englishmen for $30,000.[25] By April 1924 the old headquarters of the Press in central Hong Kong was also sold and relocated to Kowloon with the purchase of #3 Bowring Street for $52,000. Family accounts suggest that the sale allowed Xavier to concentrate on less labor intensive, and more profitable, banking services by using modern presses to produce color security notes.[26] The density and rising cost of real estate on Hong Kong island may have been an additional factor. While both the end of government printing and relocation to Kowloon could be interpreted as a departure from his father’s legacy, a cultural element also may have been involved. The Press’ new location, in fact, seemed to reflect Lisbello’s belief, as evident from the founding of the Club de Recreio in 1903, that Kowloon would remain the center of the Macanese community for the foreseeable future. Pedro’s factory, near the corner of Nathan Road and Jordan Road, soon joined a number of Macanese businesses, which supported multi-generation families, a local press, social clubs, churches, and parish schools for several decades.[27]

The final phase of the Press’ reorganization began in November 1928 when Pedro Xavier’s mother, Estaphina, granted him a power of attorney over all assets and property of the firm. This action effectively made Pedro sole owner, allowing him to begin an ambitious strategy to expand the company’s business across Southeast Asia.[28] Soon after Estaphina Xavier’s death in January 1929, the remaining assets were sold and transferred to a new company called the Hongkong Printing Press Limited, which was to be co-managed by Pedro and Cheng Tien Tau, representing the Nanyang Brothers Tobacco Company Limited, the largest producer of cigarettes in China. Other directors also reflected the new plan, including Sam Pak Ming, Comprador of the Yokohama Specie Bank, the largest bank in Japan; Leung Yan Po, Comprador of the Hongkong Electric Company Limited, the largest utility provider in the colony; and Jose Maria de Noronha, a grandson of Delfino Noronha and Head Cashier for a large French-Belgium bank, Credit Foncier d’Extreme Orient.[29] Each director controlled or influenced their company’s printing requirements, and was granted shares on the expectation of future sales to the Press.[30]

The choice of companies suggests both the promise that they held for Pedro Xavier’s business and the potential drawbacks, which may not have been clear at the time.[31] Above all, this particular group through their connection to various interests in several countries was included to impress both present and future clients. The association with the Hongkong Electric Company, for example, indicated the approval of Sir Paul Chater, the head of the utility, a wealthy land developer and socialite, and a self-made Indian immigrant who was in partnership with the Sassoons, an equally powerful merchant family. The Company was also the principal supplier of electricity to all the major banks, including the Hongkong and Shanghai Bank which employed many Macanese workers. Another formidable connection was with Jose’ Noronha, a grandson of Delfino Noronha, Lisbello Xavier’s old mentor, and the largest printer in Hong Kong. The Noronha influence among the British and wealthy Chinese reached the highest levels of government and commerce, including friendships with governors and the first Chinese and Macanese members of the Legislative Council.

Two more directors offered other connections. Cheng Tien Tau, co-manager of the new Press with Pedro Xavier, represented the Nanyang Brothers Tobacco Company Limited, the largest cigarette producer in China. The company’s principal product was a well-known brand called “Double Happiness Cigarettes”, of which Xavier expected to print at least 25% of the packaging. In a curious scheme revealed during the incorporation process, in addition to Cheng’s position as co-manager, Chan Lim Pak, Managing Director of the tobacco company and the company itself were each granted seats on the Board of Directors and partnership shares.[32] Nanyang Brothers Tobacco was controlled by Lou Lim-lok, a wealthy investor whose family obtained the first gambling and opium franchises in Macau in the late 19th century. Lim-lok’s father, Lou Kau, was a notorious gambler, investor, and philanthropist, whose downfall was well-known on the mainland.[33] His son’s cloaked presence on the Press’ board represented connections to legitimate and illegitimate Chinese businesses in both the Portuguese and British colonies, as well as rumored links to the Triads.[34]

The final director, Sam Pak Ming, represented the Yokohama Specie Bank, with branches in Hong Kong, Tokyo, Bombay, Beijing, Tianjin, and Yantai.[35] The YSB was the largest in Japan, specializing in foreign exchanges and transactions. The bank became part of a group that already included 14 other financial institutions in China through the Press’ connections in Swatow. In addition, the Japanese bank, through the Press’ partnership with Macau’s Banco Nacional Ultramarino, was now technically linked to the Kwantung Provincial Bank in Hong Kong, which printed notes for the Canton Government, and was aligned with the Chinese Nationalist Party of Sun Yat Sen and Chang Ki Shek.

This mix of commercial and political interests could co-exist in the financial world of 1920’s Asia, but began to unravel once the Japanese army invaded Manchuria in 1931. Nevertheless, the Yokohama Specie Bank was now in partnership with the Hongkong Printing Press, and was among the interconnected institutions through 1940. Each bank, like all the companies on the Press’ board, remained dependent on open borders, light financial restrictions, and a robust economy so long as their respective governments remained on good terms. How Pedro Xavier maneuvered within this environment will be the subject of the next chapter.

Next time: Part III: Crisis in Asia and the Fate of the Hongkong Printing Press, Ltd.

Notes:

[1] The majority of Macanese printers used the lithographic typesetting method, which was labor intensive and time consuming. The Hongkong Printing Press broke with this tradition after Lisbello Xavier’s death in 1909. For a concise history of Macanese printing, see the article by Hoi To Wong, “Interport Printing Enterprise: Macanese Printing Networks in Chinese Trading Ports”, Treaty Ports in Modern China: Law, Land and Power, Robert Bickers and Isabella Jackson, eds., Routledge, London, 2016:139-157.

[2] Helmut Kipphan, Handbook of Print Media: Technologies and Production Methods, Springer Science & Business Media, 2001

[3] See Carl Smith, “The German Speaking Community of Hong Kong, 1846-1918”, Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society-Hong Kong, Vol. 34, 1994.

[4] Wong, p.141.

[5] Wong, p.

[6] Wong, p.144-45.

[7] Wolfgang Keller, Ben Li, and Carol H. Shiue, “China’s Foreign Trade: Perspectives From the Past 150 Years,” NBER Working Papers, 2010:24, 16550, National Bureau of Economic Research, Inc.

[8] Ibid, p. 23.

[9] One of the initial reasons given for the flight of traders to Hong Kong and other ports was the low depth of Macau’s harbors, which could not accommodate larger steam ships. Threats from China also were fully realized with the seizure of opium factories in Canton by the Imperial government in 1839. Richard J. Grace, Opium and Empire: The Lives and Careers of William Jardine and James Matheson, McGill-Queen’s University Press, Montreal, 2014:225-239.

[10] Luis Cunha reports that local government in Macau was dominated by a small Portuguese minority, which was itself divided into factions. Among the competing interests were local Catholic parishes and the Portuguese military, which had authority over Taipa and Coloane islands. Luis Cunha, “Macau Between Republics: Neither War nor Peace (194-1918)”, e-journal of Portuguese History, University of Porto, Vol. 15, No. 1, June 2017:3

[11] Austin Coates, A Macao Narrative, Hong Kong University Press, 2009:133-35.

[12] Portugal had been going through a severe financial crisis since the late 1890s, and was forced to seek loans from Britain and Germany. Britain agreed to support the loans and protect Portuguese colonies from all enemies in exchange for colonial revenues (i.e. opium profits) if Portugal defaulted. Teresa Pinto Coelho, “Lord Salisbury’s 1890 Ultimatum to Portugal and Anglo-Portuguese Relations”, p.7, Oxford University paper, (undated): http://www.mod-langs.ox.ac.uk/files/windsor/6_pintocoelho.pdf.

[13] Cunha, op. cit. p.3

[14] Ibid, p.4-5.

[15] Quoted from Jorge AH Rangel’s translation of Manuel da Silva Mendes’ article “Macau and Hong Kong”, O Macaense newspaper, printed on December 7, 1919, which appeared in the Jornal Tribuna de Macau, September 14, 2017.

[16] The Macanese press in Hong Kong often included accounts of immigrants traveling back and forth between Macau and Hong Kong, which are less than 50 kilometers apart, for short vacations and family visits. Members of Delfino Noronha’s family, including his grandson Jose Pedro Braga who was born in Hong Kong, also lived in, or retreated periodically to Macau. See Stuart Braga, Making Impressions: A Portuguese Family in Macau and Hong Kong, 1700 – 1945, International Institute of Macau, July 2015:299-303.

[17] Francisco, a Macanese through his mother, is listed as “Francis Paul Danenberg” in the list of jurors printed in the Hongkong Government Gazette dated 19th Feb, 1904, as archived by Hong Kong Government Reports Online. Francisco’s brother, Antonio Maria Danenberg, was married to Glafira Antonia Xavier, the daughter of Pedro’s aunt and Lisbello de Jesus Xavier’s older sister, Maria Francisca Xavier. Reference: “Francisco de Paula Danenberg, 1874 (Hong Kong) – 1917 (Shanghai)”, as listed on Macanesefamilies.com, an on-line genealogy based on Jorge Forjaz’s Familias Macaense, 1996 and 2017.

[18] “A New Direction: the Hongkong Printing Press, Lithographers 1888 – 1929”, unpublished manuscript, family histories of the Sarrazolla and Xavier families, compiled by Anita M. Xavier, Queensland, Aus. 2000:2.

[19] Ibid, p.2

[20] Family sources suggest that the HKPP also printed bank and account holder checks and script. Ibid. p3.

[21] Cai, Xiang-yu, “Missions, Needlework and Gender”, in Christianity and Gender in South-East China : the Chaozhou Missions (1849-1949), 2012, University of Leiden Repository. He writes: “Between 1900 and 1914, the needlework industry began to grow and workshops were established in Swatow, mostly using investments by Chinese dealers.”

York Lo, in the article: “The Needle, the Bible and “Our People”: Chiuchow Christians and the Swatow Lace Industry in Hong Kong” , October 30, 2017, http://industrialhistoryhk.org/swatow-lace/#comment-33819, provides the historical context: “In the late 19th century, American missionaries such as Lida Ashmore and Sophia Lyall introduced Western needlework techniques such as drawn-thread, cross stitch, crochet and embroidery to women in the Chiuchow region in Guangdong province. The hand embroidered table linens, silk lingerie and handkerchiefs coming out of the region became known as “Swatow lace” or “Swatow drawn work” after Swatow, the biggest city in the region. Starting out as peddlers of Swatow lace made in small workshops, Chiuchow Christians organized themselves into companies and business took off in the 1910s when the War in Europe disrupted production in European cities such as Venice and buyers from the West discovered Swatow lace which was equal if not better in quality yet cheaper than machine-made embroidery. … By 1941, the export value of the Swatow lace industry exceeded US$12 million (with over 70% going to America) and employed an estimated 300,000 people.”

[22] The following is a list of banks contracted by the Hongkong Printing Press from 1913 through 1928, as recorded by Anita M. Xavier, op. cit. in the “New Directions” manuscript:

1913: Chan Wai Seng Bank, Chewsang, (Kwangtung);

1914: Kwan Chin Chong Private Bank, Guo Hong Yu Private Bank, Tan Hua Loong Chong Bank, The Commercial Bank, The GWA Swarmwun Yiack Private Bank, Guandong Private Bank

1916: Lee Yick Cheong Bank

1918: Banco Nacional Ultramarino (Macau)

1922: Hon Tat Lung Kee Bank, Hung Tai Chong Bank, Chin Hong Local Bank, Yee Seng Chong Private Bank

1928: Zhi Fa Private Bank

[23] Private letter written on Hongkong Printing Press Limited letterhead, dated 2nd August 1943, to the British Consul in Macau. Xavier family archive, Anita M. Xavier, 2000.

[24] Company records indicate that printing contracts were frequent through 1940.

[25] The buyers were Messrs. C. Burnett and V. Labrum, who agreed to payment in monthly installments of $700 at 7% interest.

[26] Xavier family archive, Dr. Anita M. Xavier, 2000.

[27] See Fr. Zinho Gozano’s account of his old Kowloon neighborhood in: THE LIFE AND TIMES OF FATHER JOSÉ “ZINHO” GOSANO, UNIAO MACAENSE AMERICANA Bulletin, Apr-Jun 2011 Vol 34 No 2. Together with the previously mentioned Club de Recreio, other associations included the “Little Flower Club”, a woman’s organization that raised funds for the Church. For a time Mr. Nolasco da Silva, the former Treasurer and Head of Macau’s Municipal Council (Leal Senado) was editor of the Echo do Povo, a Portuguese weekly paper published in Hongkong, and the principal contributor to the weekly papers, O Macaense and the Echo Macaense, published in Macau and distributed in Hong Kong. See Twentieth Century Impressions of Hongkong, Shanghai, and other Treaty Ports of China, Hong Kong, 1908: 809.

[28] “A New Direction”, Xavier family archive, Anita M. Xavier, 2000.

[29] “A New Direction”, Xavier family archive, Anita M. Xavier, 2000. Chater apparently gave his approval as Pedro Xavier was planning his reorganization of the Press sometime between April 1924, when HKPP headquarters was moved to #3 Bowring Street to concentrate on currency printing, and Chater’s death in May 1926. I surmise that is the period when the new strategy to concentrate on bank currencies and other larger orders was first anticipated and initially implemented. Chater’s successors gave approval through the next phase when Pedro Xavier officially created the new HKPP Ltd. in January 1929, and in exchange, officially granted the board seat and company shares to the electric company.

[30] Pedro apparently expected at least 25% of all packaging for Nanyang Brothers cigarettes to be performed by the Press. (family manuscript)

[31] http://www.fundinguniverse.com/company-histories/hongkong-electric-holdings-ltd-history/ (History of the Hongkong Electric Company Limited) See also Twentieth Century Impressions of Hongkong, Shanghai, and other Treaty Ports of China, op. cit.p. 168.

[32] “A New Direction”, Xavier family archive, Anita M. Xavier, 2000.

[33] Lou Kau came to Macau with his family from Guangdong in 1857 and opened a private bank ten years later. He then invested in pork from his home province and sold the meat in Macau. In 1881 Lou was granted the first opium franchise, followed by the gambling concession for “Fan Tan”, a traditional Han Chinese game, in 1882. He spent the next two decades supporting charitable projects among the Chinese, including hospitals and schools. In 1906, however, under pressure from creditors in Guangdong Lou committed suicide, elevating his son Lou Lim-lok to the head of the family business. Mark O’Neill, “Macao Mansion Hides Story of Wealth and Tragedy”, Macau Magazine, January, 2010, Issue No. 2.

[34] “The History of Gambling in Hong Kong and Macau”, in Chi Chuen Chan, et. al., Problem Gambling in Hong Kong and Macau, Singapore, 2016:13-14.

[35] “A New Direction”, Xavier family archive, Anita M. Xavier, 2000.

Hi! I am a resident of Beihai (formerly Pakhoi) and conducting research into the history of Pakhoi during the Treaty period of the 1800’s to 1950.

I have come across a reference to Glafira Antonia Xavier Danenburg dying in Pakhoi on the 5th August 1919.

I was hoping you might be able to assist me with my enquiry. I was wondering what Glafira was doing in Pakhoi at the time and whether the family had a business in Pakhoi.

I look forward to establishing contact with you.

Kind regards,

Ian Blanden

Hello Ian,

Sorry for very late reply. I may have some information, but it may take me a few weeks to respond back.

Regards,

Roy

Hi Ian, I have very little information about Glafira Antonia Xavier Danenburg. She was born in Macau on August 17, 1876, the daughter of a doctor and the older sister of the Hong Kong printer, Lisbello J. Xavier. She was married in Hong Kong to Antonio Maria Danenburg around May or June, 1903, but her only child, Francisco Xavier Danenberg, was born in Shanghai in April 1904. As to her death in Pakhoi in 1919, I can only speculate it was because her son Francisco was likely in business there, in proximity to Hong Kong where his uncle, also named Francisco, was in a partnership with Pedro Xavier, who inherited directorship of the HongKong Printing Press from his father Lisbello in 1909. The elder Francisco (de Paula) Danenberg, who was Antonio’s brother, was the manager of the Royal Aerated Water Manufactory Co. Pedro Xavier was a director. Pedro’s company printed the labels for his cousin Francisco’s company. This information is mentioned in my article on the HKPP here: https://macstudies.net/the-hongkong-printing-press-part-ii/. I hope this will help your research.

Best regards,

Roy